As you approach Santa Fe, you may notice hillsides covered with shrubby piñon trees. Nothing quite says you are in the Southwest as the crisp air carrying the scent of piñon pine. The smell of it burning wafts across the plaza in downtown Santa Fe. Plenty of stores carry piñon pine specialties, like piñon brittle, candies, nuts roasted with chile, and piñon coffee.

This species features in the traditions, legends, and ceremonies of many Southwestern cultures as described in a 1930s pamphlet from the National Parks Service. It may have been a major source of protein for Native Americans, including the Utes. For a modern discussion of the significance of the piñon to the Apache, this short blog includes a video and mentions piñon branches as smudge sticks. According to the site Pinenut.com, the nuts have had an economic benefit to the Navajo and in the 1930’s provided “more than the combined value of both rugs and silver which they produced.”

Piñon pine, Pinus edulis, is also known as Colorado piñon, Pinyon, common pinyon, New Mexico pinyon, Colorado pinyon, mesa pinyon, two-leaf pinyon, two-needle pine, nut pine, Rocky Mountain pinon, and Pino dulce. The preferred spelling, piñon, is Spanish and is interchangeable with most of the variations above. Although the USDA shows the trees throughout the Southwest, other sources indicate they are found primarily in Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico. This discrepancy could be related to the existence of related species such as the single-leaf piñon, Pinus monophylla. Sibley* and others note the various species hybridize, making identification difficult.

Pinus edulis, the state tree of New Mexico, are “bushy” trees. They are slow growing but long-lived, possibly living up to 1000 years. The oldest verified tree was dated at 973 years, while the largest is located near Santa Fe, NM. As an alternate name suggests, this pine has two leaves in a fascicle, with the needles usually between 0.6 and 2.0 inches in length. The cones of the piñon are small, about an inch in diameter, and very round.* This species may not produce any cones until the trees are a quarter century old, with good seed production not starting until the specimen is 75 to 100 years old. As the fertilized seeds are comparatively heavy and not disbursed far by the wind, the species is dependent on birds to sow the seeds. Four species are primarily involved in this task: Clark’s nutcracker, Steller’s jay, Mexican jay, and the pinyon jay.

Although the seeds are what this species is known for, it is hard to beat its wood for a fire. The aroma is distinctive and quite pleasant. According to many sources, it provides nearly as many BTUs as hardwoods and has been called the “hardwood of soft woods.” Unfortunately, most sources lump piñon in with other pines, which might make sense on the national level. The benefits of burning in areas where it is available should not be overlooked. It is often cited as the best wood for chimineas.

The sap, or pitch, of the piñon has been used by Native Americans in the Southwest for various tasks such as mending cracks in bowls, waterproofing baskets, and as an adhesive. The medical uses of piñon are, in general, lumped in with the properties of other pines. A tea of the needles is used to ward off scurvy** or for its expectorant effect***. The inner bark could be used to dress burns and other skin conditions. Piñon is said to have an antiseptic quality. These last two factors are why it is used to make natural salves today. Mother Earth News suggests the antiseptic qualities make it a good bathroom cleaner and air freshener.

Today the nuts themselves are the stars of the piñon tree. Multiple places proclaim their nutritional value, from saying they are as protein rich as beef, to suggesting they may be a good source of polyunsaturated and monosaturated oils.

My first encounter with piñon nuts involved the difficulty of shelling them. My friends who had gone to college in Santa Fe, insisted the best way to crack them was with your teeth. Although this method is okay if you are going to ingest them raw or roasted for yourself, the idea of cracking nuts with that method and cooking with them for others seemed objectionable to me!

According to an undated article in New Mexico Magazine, a secret shelling machine was invented by the founder of Buffett’s, an Albuquerque mainstay since 1956. The article also states you can purchase shelled piñon from them but I was not able to find any for sale on their site at this time, shelled or not. You ARE still able to buy piñon candy from them, including piñon brittle.

Numerous sites discuss the differences between “hard shell” nuts, those which are from Pinus edulis, and the soft shell nuts, Pinus monophylla, or Nevada nuts. The nuts of Pinus monophylla are larger, more resinous, and not considered as tasty. Euell Gibbons may have proclaimed the piñon nut “the most palatable wild food.” Many websites warn against buying Nevada nuts when you are after piñons. The New Mexico Piñon Nut Company ships nuts. Pinenut.com explained the 2021 supply is limited as the quarantine kept pickers out of the trees.

Not only the Native American population of the Southwest harvests piñon; many Hispanic families also gather the nuts in the fall. In many areas of New Mexico you see cars parked along the interstate and people scurrying amongst the trees. Harvesting your own nuts is the most economical. Although it is legal to gather nuts for your personal use in certain areas, it is best to know the laws. Some people shake the trees to remove the nuts or cones, but the traditional method is to pick off the ground as seen in this short video. Less traditional methods of picking and preparing nuts are discussed in this article where the author suggests breaking open the nuts with a rolling pin.

Although most articles mention eating the pine nuts raw or roasted, recipes for their use abound. Fancy recipes such as pine nut soup, pine-encrusted pork, and a chocolate tart are including in this article from New Mexico Magazine. A number of recipes including candy and cookies can be found here. Native American Feast Day cookies feature piñons.

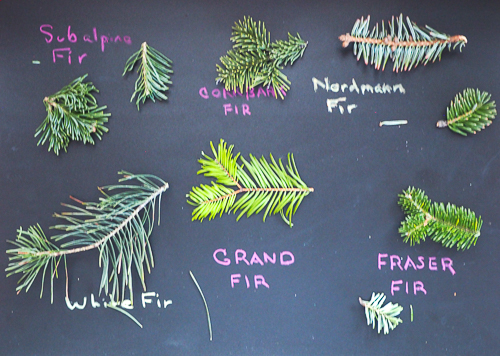

The piñon pine has also been used as a Christmas tree, living or cut. As is true for other features of the piñon, most lists of best trees for Christmas neglect to mention the species. New Mexico State University recommends them as having a good shape and says they are easily available for residents to cut. Every once in a while another publication will mention this conifer as a holiday possibility such as this bulletin from Washington state, which seems a bit out of their natural range!

A recent article discusses threats against piñon nuts and the trees themselves: climate change and cheap imports from other countries. Recent droughts have weakened the trees, which then are attacked by the ips, or bark, beetle. A study from California found higher temperatures decreased the viability of piñon pollen., while other studies have implicated heat death as the cause of the loss of between 40 and 80 percent of the trees. Not only are the trees and nuts endangered, but up to three quarters of the bird population may have disappeared in a decade.

Although it does little to solve the larger problem of the demise of the trees, it is still possible to use the logs as firewood if measures are made to destroy remaining beetles. In another glimmer of hope, the study mentioned above about the effect of heat, mentions a fungus that often grows with piñons may confer some drought protection.

By some reports nut harvests have decreased in yield by nearly seventy-five percent in less than fifty years. Indeed not all of the decline in piñon economy can be assigned to the change in climate. More than one article mentions the penchant for bulldozing trees in favor of ranchland or mineral and oil development as another factor leading to the decrease in productive piñons. The lower cost of imports doesn’t help the case for gathering the increasingly scare native product, either. In 2020-21 the cost of the nuts soared due to Covid-19 keeping pickers away.

In a 2014 publication, Rocky Mountain Forests at Risk, the authors discuss the importance of iconic trees in the Rockies and show possible scenarios related to drought, heat, and wildfire. They state the piñon-juniper woodlands are the most extensive type of forest land in the United States. They also mention piñons cultural significance as well as its role in water quality.

The Colorado pinyon (Pinus Edulis) can be found in City Park just northwest of Club Tico and across the road, near a power box. There are only two conifers in that area, and both appear to be piñon pines.

* David Allen Sibley, The Sibley Guide to Trees (Alfred A. Knopf, 2009, p.12)

**Linda Kershaw, Edible & Medicinal Plants of the Rockies (Lone Pine Publishing, 2000, p.36)

*** Michael Moore, Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West (Museum of New Mexico Press, 2003, p. 196)